The Rogue River is a classic multi-day river trip enjoyed by thousands of people every year. Protected as one of the original eight Wild and Scenic Rivers in 1968 this gem offers great rapids, spectacular camps, awesome side hikes, and so much human history.

One of the most famous places on the Rogue River is Blossom Bar Rapid, commonly referred to as “the most expensive rapid in the West.” You can find countless stories and YouTube videos of success and mishap with a quick search of the internet. Sit around any camp river with river runners and there will be at least one good story about the rapid.

History

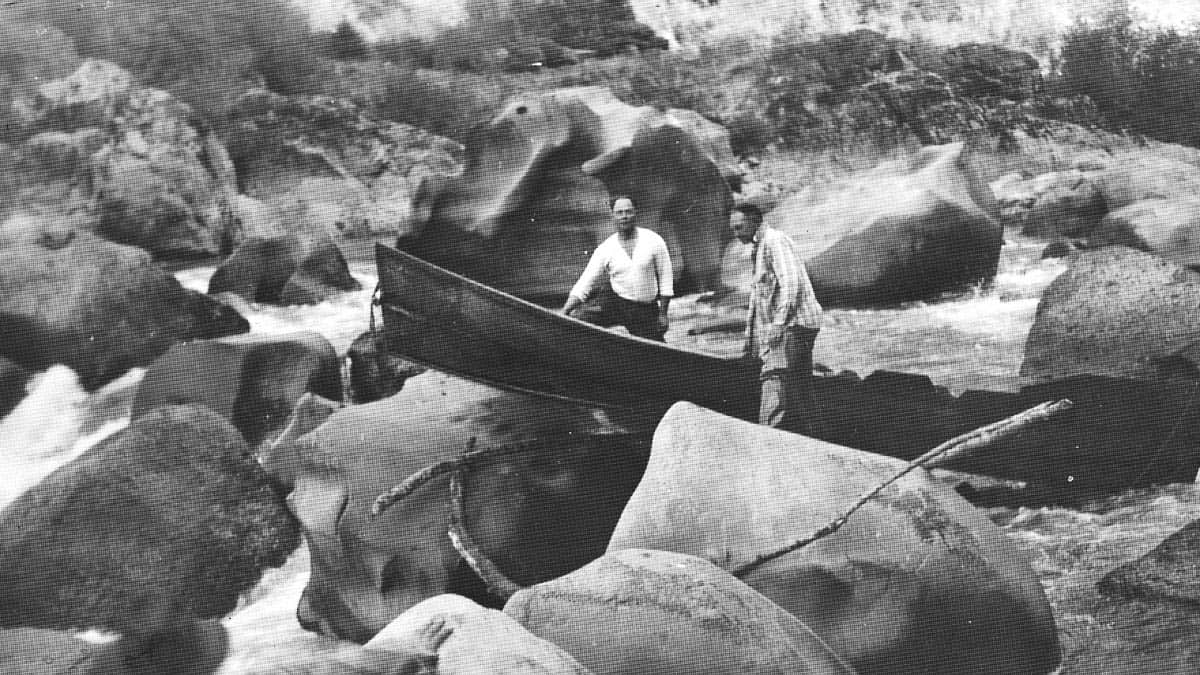

The famed, feared, and infamous Blossom Bar was once an unnavigable boulder garden that required a portage and kept many boatmen from making the trip down river. That didn’t keep miners from setting up a stamp mill to process gold ore from the upstream Mule Mountain Mines. You can still find mill remains, tailings, and the mortar box near the foot bridge on the Rogue River Trail. Fast forward to the 1930s-1940s to Glen Woolridge perfecting their methods for making the river more navigable.

Dynamite sticks in a sack weighted with rocks was the preferred method for clearing rocks and large boulders for a navigable channel. Many of the rapids on the Rogue have been treated with this method to make it possible for boats to travel down stream.

Naming a Notorious Rapid after a Flower

The fragrant and vibrant white to pink flowers of the Western Azalea, Rhododendron occidentale, that bloom in the spring helped name this part of the canyon. As one of two native deciduous Rhododendrons in the west the Western Azalea has specialized to grow in serpentine soils sounds in the Siskiyou Mountains of Northern California and Southwestern Oregon.

The Classic Line (Left Side)

The traditional line taken through Blossom Bar starts on river left pulling the boat across a strong eddy line and into the eddy formed by the large boulders in the middle of the river.

Timing is key here as to early and fast you may bounce into the picket fence, too late and slow you may end up in the picket fence. The big debate when rowing is downstream ferry angle or upstream ferry angle.

Downstream Ferry Angle

A downstream ferry angle gets you moving with the current with some speed to break through lateral waves and into an eddy. This can be a tricky move as you are coming into the rapid backwards looking over your shoulder with your stern pointed towards where you want to go.

Pulling hard with the current can get you to cross that eddy line nice and quick. However, getting into the eddy too early can cause you the bounce off one of the guard rocks and into the picket fence. Crossing that eddy line too late and you have missed the move entirely and are heading toward the picket fence.

Upstream Ferry Angle

The upstream ferry angle has your boat pointed downstream, pulling away from danger. You are fighting the current here and really need to work hard to get across the eddy line.

The upstream ferry angle takes some timing, as well as some muscle. This move has you looking downstream and doesn’t feel as expose to the picket fence as the downstream ferry angle. You still need to watch out for guard rocks that will bounce you into the picket fence. If you aren’t going to make the move and are headed toward the picket fence you are at least facing the danger.

The Picket Fence

Not your “American Dream white picket fence” here. This jumble of under cut rocks that sets the boundary for the classic line is the one place you want to avoid. This pile of rocks come into play when you miss “the move” and don’t make it into the eddy. If the water is high enough you are able to float right over all of the danger but as the water drops this is where boats get perched, wrapped, or may flip.

Wrapped boats in the picket fence make for a great and difficult boat rescue. The easiest access and place to set up anchors to access the stuck boat is from the left shore. However, pulling your boat to the left bring it right into what some refer to as “the room of doom,” an eddy with only small channels of water flowing through. This makes it pretty difficult to get a heave gear boat out.

It is a really long distance to the right shore, and puts ropes across nearly the entire river. Getting ropes to the stuck boat requires some long heroic throw bag tosses and lots of rope.

Another option is in the middle of the river, requiring some risky boat maneuvering. Once safely on the rocks above the stuck boat there are some large rocks to build anchors, the throw bag toss relatively short and straight forward, and hopefully the boat is pulled off and able to go down stream.

After The Move

Whether you choose the downstream ferry or upstream ferry there is still lots of work to be done. Once in the eddy make your way down the “beaver slide” and pick your way down the rest of the rapid.

There are many rocks in the rapid to get your boat stuck on so pay attention. The huge boulder near the end of the rapid called “Volkswagen Rock” can be tricky. Pick right or left and stay with that plan. I have seen many boats highside on the rock after a last second decision to go the other way.

The Uncommon Line (Right Side)

While most people are pretty focus on “the move” the right line can easily get overlooked. The right line has it challenges and isn’t always an option.

You may take a look and think “oh it just looks like a little drop, avoid a couple rocks at the bottom, and it is all done.” That is sort of how it goes, but those rocks at the bottom on the right come really quick and like to grab boats. I suggest saving it for water levels above 3500 CFS where the rocks are a bit more covered up.

This complex boulder garden challenges boaters today, and even keeps some boaters from venturing down the canyon. Causing raft trips some trouble and lost gear often gets this rapid on the list of most difficult rapids for rafters. Scouting this rapid is a good idea, and offers a great view of the river.